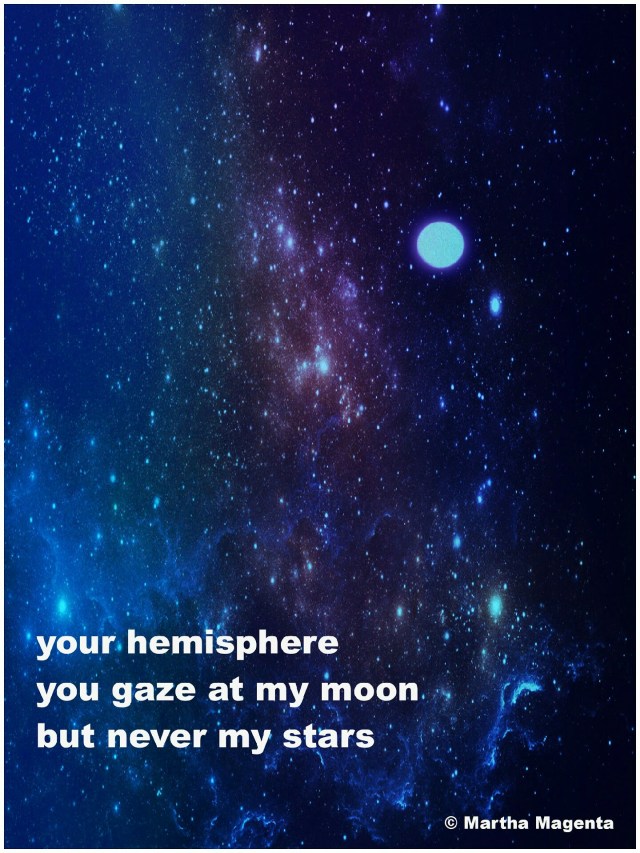

Each word in this shahai (haiku with a photo) is significant and carries many dimensions. Though the haiku can be taken literally, as two lovers far away from each other, and them gazing at different night skies, the metaphorical quality of the haiku easily comes through.

The tone of the haiku is almost argumentative. It is quite personal, like the reader is listening in on a couple’s heated conversation. “hemisphere” can mean literally the hemisphere one is in, or the hemisphere of the loved one’s brain, or in a more abstract sense, the perspective of the loved one.

“gaze” is not a light word here. From the tone of the haiku, it seems be used in a negative manner.

What I got from this haiku is that the poet does not like how a certain loved one perceives or notices only the exterior or holistic points in the poet, while the loved one is missing the “stars,” the small things that create the larger picture of who she is.

And what a large entity we have in the photo, of which appears to be a panorama of a galaxy or two (or maybe infinity itself, because we are infinite, right?). I believe this shows the wideness the poet wished the loved one saw in her.

Though there seems to be more than enough pronouns, the haiku is so engaging that I didn’t even consider it a problem.

The wording is concise and it is well-phrased. I would move this to being a senryu rather than a haiku based on its tone. But ultimately, the feeling behind the poem is more important than the categorization.

– Nicholas Klacsanzky (Ukraine)