another pear

rots in our fruit bowl

the promises

we choose

not to keep

– Tia Nicole Haynes (USA)

Published in Frameless Sky, 11

The pear could be symbolizing comfort and inner peace which one gets through the sweetness of life. This tanka perhaps revolves around the choices we make to get that inner peace.

So, another pear rotting in the fruit bowl means the circumstances and choices are not appropriate for gaining inner peace and comfort in life. We make certain promises in life to do things that bring happiness and peace in our lives–especially the ones where the focus of control is our inner self. But, due to certain circumstances, we are not able to carry out those promises we make with ourselves. That makes life so uncertain in many ways that we forget to taste the inner peace, as it gets spoiled and rotten by limited choices.

There is a continuous process of striving for inner peace, which is the ultimate goal of our lives and we really wish to keep things in line with our ultimate goal and make promises every year for it. But, life in certain ways puts us through trials and we forget that ultimate goal.

In terms of sound, the letter ‘o’ could indicate the life cycle that makes us deal with different matters of life but also forgetting the ultimate goal.

– Hifsa Ashraf (Pakistan)

This tanka contains a comparison: the promises we choose not to keep are like another pear rotting in our fruit bowl. They are visible, the stench is clear, yet we decide not to abide by our word. This is a part of human nature. Though promises that are left behind stare us in the face, we somehow have the will to let them go sometimes.

The degradation of a pear is an apt symbol: they are sweet but easily bruise and go rotten, just like promises.

Like Hifsa, I enjoyed the “o” sounds in this tanka. I also thought the “r” sounds lend to a serious tone. Additionally in the technical vein, the poet is highly efficient with her words and allows each line to breath in its simplicity and power.

– Nicholas Klacsanzky (USA)

If you enjoyed this tanka and commentary, please leave a comment.

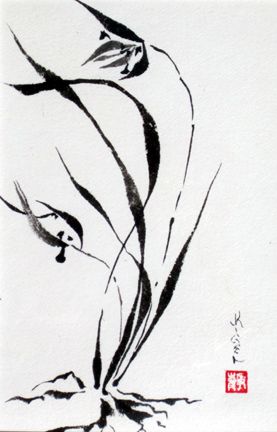

Painting by Terry Wise