Words and image © Brendon Kent (UK)

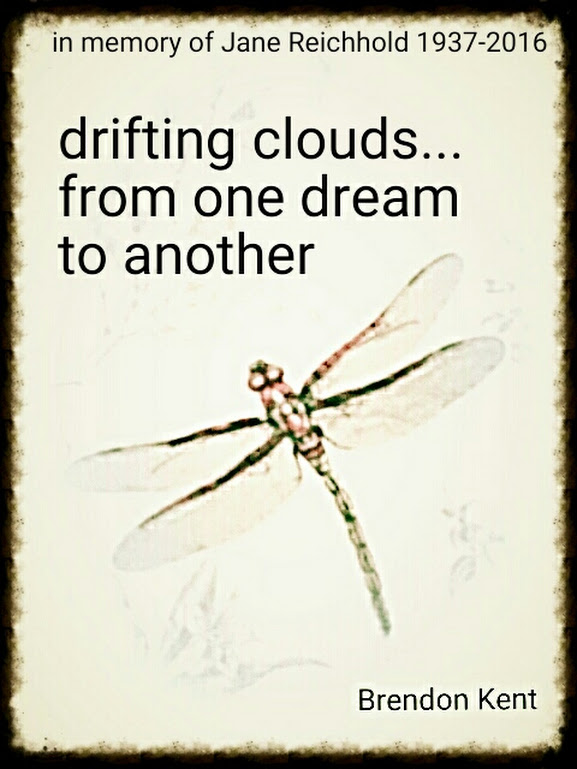

For the context of this haiga, or haiku and art combined, I should tell who Jane Reichhold was.

Jane Reichhold was a popular and key member of the haiku community. She was the editor of Lynx journal of haiku, tanka, and renga, and the owner of the site Aha Poetry, where a great amount of reading materials on haiku and related forms are held online. She wrote many famous books on haiku, such as Basho: The Complete Haiku, Writing and Enjoying Haiku: A Hands-on Guide, A Dictionary of Haiku, and many more influential books. She also was the recipient of the Museum of Haiku Literature Award [Tokyo] twice and the Merit Book Award twice.

It was announced that she passed away on August 5th, 2016. Many tribute haiku and articles were written for her, as she trained and influenced so many people through her essays and poetry. This haiku by Brendon Kent is a fine example of a tribute haiku for Jane.

This haiku has a clear juxtaposition and is written in a more traditional style, which I think is a prudent choice for the tone of a tribute. The poet is comparing drifting clouds to traveling from one dream to another. This juxtaposition is complemented by the image of the slightly blurred dragonfly in flight. In haiga, the image and text usually are not directly connected, but hint at each other. Brendon has done a superb job making this connection indirectly, creating a defined mood.

The use of the ellipsis shows a carrying on and delineates the two parts clearly. I think without the ellipsis, the meaning could change, and maybe Brendon wanted a more focused reading of his haiku.

I don’t know why exactly, but I feel emotional reading this haiku. It looks straightforward, but there is a definite emotion behind the words. Maybe it is the context or the solemnity with which the pacing of lines are written, but it charges me with emotion and maybe a sense of awe.

Let’s great back to the clouds. Clouds are high in the heavens, as you can say, and are an apt metaphor for Jane. She was a selfless person and committed to write poetry that uplifted people. The drifting, I believe, is a metaphor for passing into another life. The wind making the clouds drift could be a symbol for the universal spirit that is often expressed as wind in spiritual doctrines. Maybe the cloud is a symbol for Jane in the afterlife, soon to rain and bring about a new life of her own in a distant place.

The dream could be the illusion of life. Most spiritual traditions agree that we are not this body, emotions, or mind, but a pure spirit. It seems these lines are a kind of reassurance and a kind of detachment as well. This process of life and death are only transitions of the mundane, and maybe we all wake up to our spirit in between (though some say it is better to realize the spirit while living).

Or, the poet could be simply stating what happened to him. Maybe he took a nap on a forest walk, or on his backyard, and woke up to seeing drifting clouds after experiencing transitions to and from different dreams.

Haiku are usually objective reporting of what is happening, but can be seen as metaphors and symbols for much more. And knowing Brendon Kent’s work, he enjoys creating layers of meaning in his work, so it is probable that he wanted to portray both the spiritual and mundane.

On the level of sound, the “o” sound in “clouds,” “from,” “one,” “to,” and “another” create a wispy feeling for the reader, akin to clouds. It is great when the reading of a poem accurately reflects its content. The words without”o” are “drifting” and “dream,” which have alliteration and are both key words in the context of this haiku. Leaving these words as the only ones without an “o” sound makes them stand out more, which draws our attention to them more.

Though many fine tributes for Jane Reichhold have been written since her passing, this is one of the finest I have read. Wherever Jane may be now, I hope she is reading this tribute, and many others.

– Nicholas Klacsanzky (Ukraine)