silver lining—

what the storm takes

from the magpie’s fable

— R.C. Thomas (UK)

(Joint First Place, Sharpening the Green Pencil Haiku Contest, 2022)

Commentary:

Magpies in various fables symbolize being prudent, wise, and cunning. A magpie in a fable, no matter who wrote it, is interesting and has a central place in the story. The bird itself is known for its self-centered nature that it uses to protect itself from threats. This haiku has cleverly placed the nature of a magpie by referring to a fable that centers on it. I may consider the fable as an allusion to empower the rest of this haiku. Irrespective of the discussion about the magpie being considered a good or a bad omen based on natural history, old literature has used this bird significantly in stories, poems, anecdotes, and fables, which shows how frequently it is connected with the daily lives of many people as a social bird.

“Silver lining” is symbolically used to represent how easily we can get lessons from the birds around us, perhaps. The magpie, being a prudent and cunning bird, knows how to get something beneficial out of a difficult time, which is no less than a storm. I see a problem-solving aspect here where the poet tries to justify the nature of a magpie by giving it a central position and trying to convince us to see how things work when we use our minds actively and wisely no matter how hard the situation is. It also gives us a sense of realization that we as people are provided with many examples in our surroundings that can help us learn something positive. Just like in old times, people used to write fables inspired by nature and the creatures in their surroundings.

Now coming to the imagery of this haiku, I see it as black and white where the silver lining (light colour) blends with storm clouds (dark colour), and both are linked with the colours of the magpie. This can show how deeply our thoughts are linked with the shades of life and how they can reshape our approach to life.

The personification of the storm in this haiku is interesting. I feel the storm is animated and full of Spirit.

It seems the main message in this haiku is that words have power and have been affecting both humans and non-humans over thousands of years. It seems it is not only the words themselves but the energy, principles, and intentions behind the words that have significance and power. Along these lines, there are many interesting Indigenous myths and stories involving various birds, floods and storms born out of a deep reverence and respect for the Earth. I suspect there are fables about birds and storms in every culture.

In regards to the storm in this haiku, in the book Black Elk Speaks, the Indigenous Medicine Man named Black Elk talks about his experience being in a colonized city for the first time. He says: “I was surprised at the big houses and so many people, and there were bright lights at night, so that you could not see the stars, and some of these lights, I heard, were made with the power of thunder” (Neihardt, page 135). In the notes, it says: “The Lakota word for electricity is wakhágli ‘lightning,’ hence “the power of thunder” (Neihardt, page 323). In other words, Black Elk had only seen electricity before in the form of lightning and he called storms and lightning Thunder Beings as a form of spiritual energy to be respected with reverence.

In another interpretation, the storm in this haiku could possibly be a mental storm, perhaps caused and/or partly influenced by the fable itself. Along these lines, I think about the mistranslations and misinterpretations in some fables, and how words can be misused and abused. Unfortunately, as one example, some of the fables and metaphors found in certain religious texts are severely mistranslated and include stories of violence and dominance with a heavy emphasis on sin, fear, punishment and “my way or the highway” thinking. Furthermore, Divine Power is expressed in certain religious texts using only male “He” and “His” pronouns, consequently degrading the beauty and power of women.

This is a consequence we all pay the price for and has clearly done a great deal of harm. In my view, if both men and women embrace the spirit of sensitivity and compassion within themselves, then we have a chance to make significant progress.

Despite the negative consequences of certain fables, the silver lining in this haiku tells me the poet sees the bigger picture, and that the fable itself likely includes very challenging circumstances we can learn from. In short, depending on the fable, I see a potential mix of both negative and positive outcomes. Reading the fable itself could also perhaps inspire us to (pun intended) brainstorm better ones. If we look at the definitions of fable, we have:

1) a short tale to teach a moral lesson, often with animals or inanimate objects as characters; apologue

2) a story not founded on fact

3) a story about supernatural or extraordinary persons or incidents; legend: the fables of gods and heroes.

4) legends or myths collectively: the heroes of a Greek fable

5) an untruth; falsehood: this boast of a cure is a medical fable

6) the plot of an epic, a dramatic poem, or a play

7) idle talk

Source: Fable Definition & Meaning | Dictionary.com

These definitions give us a better idea of what a fable is. In short, I see the word fable as a psychological portal into the human psyche.

The good news is, if the mind is conditioned, it can also be unconditioned. There are, indeed, many ways of seeing the world and many different ways of life. Even if someone has a specific philosophy or spiritual path, my sincere hope is they are also open-minded to other respectful, meaningful philosophies.

I also strongly feel Mother Earth has many gifts we can all learn from. One of the greatest lessons I’ve learned from Mother Earth is the power of silence. It seems there is great wisdom in being quiet in Nature. This reminds me of a quote by Bashō: “Follow Nature and return to Nature.” Along these lines, when I read “magpie’s fable,” I initially heard stories of the bird’s life through his or her songs vs. human-made fables about the magpie.

As a final interpretation, if taken literally, I can see light-hearted humor in this haiku as the storm has no ears to hear our human-made stories, nor does the magpie have English words to form the fable. The storm continues, and it will eventually pass, with or without humans and our stories.

Regardless of our interpretation(s), this haiku explores the deep psychological space between the human mind and Mother Earth. I think it also reminds us to be careful with our words and to be mindful of their effects and possible interpretations. An interesting and important haiku.

— Jacob D. Salzer

Hifsa and Jacob have explored this haiku in great depth. I’ll briefly comment on the kigo, kireji, toriawase, pacing, and sound of this poem.

The kigo, or seasonal reference, of this haiku could be between August and October since magpies are most active during this time. This makes this an autumnal haiku. The storm adds to this assumption.

The kireji, or “cutting word,” in this haiku is shown as the em dash in the first line. It successfully separates the two parts of the haiku while also giving us time to pause to imagine a silver lining.

The toriawase, or juxtaposition, is the association between the natural and fictional world. The wisdom and ingenuity of the magpie in fables are compared to a silver lining during a storm. A wonderful thought.

In terms of pacing, the length of the lines is a bit different than the standard in English-language haiku because the third line is long while it is usually short. However, the poet wrote the haiku organically and well-framed, because if the first line was placed as the third line, it would not be read as well. Also, the word “takes” is a fine place to cut the line to create suspense.

Finally, looking at the sound of the haiku, the many “i”s and “l”s create a combination of sharp and soft notes. This relates well to the rumble of a storm and the lesson of a fable.

A unique and fresh haiku with significant overtones.

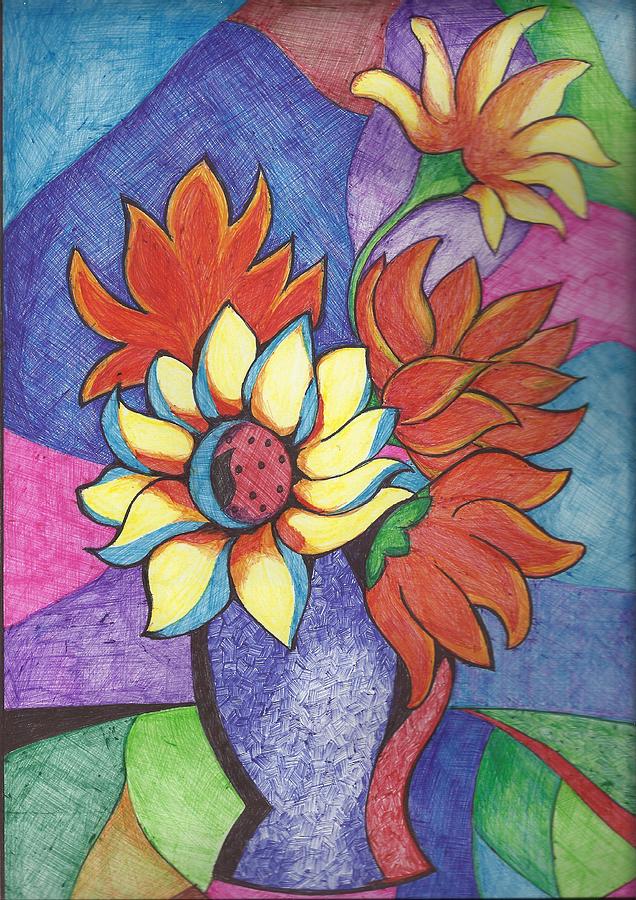

“Fantasy Magpie Fable.” Acrylic on deep wooden support by John Penney.