meditation music …

a kitten’s purr slips

into incense

— Samo Kreutz (Slovenia)

THF Haiku Dialogue, November 2025

Commentary from Hifsa Ashraf:

This haiku resonates deeply with me, especially since my recent collaborative book, Beyond Emptiness, explores themes of mysticism and spiritual transformation.

The opening line, “meditation music,” immediately evokes a serene, introspective space. For me, it echoes the tones of Sufi music or soft instrumental melodies—sounds that captivate the senses and guide the soul toward mindfulness. Such music plays a vital role in calming the nerves and synchronizing one’s rhythm with the stillness within.

The second line, “a kitten’s purr,” introduces a gentle, intimate sound—subtle yet profound. I interpret the kitten’s presence as symbolic of a beginner in meditation: quiet, curious, and softly aligned with the spiritual energy. Purring suggests delight, warmth, and safety—a sensory harmony that seamlessly blends with the meditative ambiance. It reminds us that the healing power of sound affects not just humans but all sentient beings.

The poet concludes it beautifully with “slips into incense,” which is both poetic and mystical. There’s a beautiful synesthetic quality here, a merging of sound, scent, and motion. The phrase “slips into” suggests a gentle transformation, a shift from the tangible into the ethereal. It reflects that moment in meditation when physical sensations dissolve, and one is immersed in the intangible. The incense symbolizes this spiritual diffusion where worldly concerns fade, and one melts into a deeper, more satisfying stillness.

Altogether, the haiku captures a sacred moment where the boundaries between body, mind, and spirit gently blur.

queueing for coffee

an elderly man

counting his change

— Tuyet Van Do (Australia)

Kokako 43, 2025

Commentary from Jacob D. Salzer:

This is an important haiku for a variety of reasons.

Firstly, this haiku shows a fast-paced lifestyle that coffee is often associated with, and the sheer demand for coffee. While there is non-caffeinated coffee available, most coffee has caffeine, which is known as an addictive drug. Not all people who drink coffee are addicted, but many people are. This could transfer to the interpretation that some people seem to be addicted to a fast-paced lifestyle, thinking that faster is always better. However, some people also seem to move faster as a survival mechanism due to low-wage jobs and rising costs of living. By moving faster and sometimes working multiple jobs, there is an opportunity to make more money.

While drinking coffee in moderation has health benefits, the added sugar to specialty coffee beverages, such as lattes, can have serious health consequences when consumed regularly over time, and can lead to diabetes mellitus, inflammation, and cardiovascular diseases, which can be fatal. According to the World Health Organization, in 2021, ischemic heart disease was the #1 cause of death worldwide, and diabetes mellitus was the 8th leading cause of death (source: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death). There are also often negative health consequences that come with a fast-paced lifestyle, including increased stress, and not activating our parasympathetic nervous system enough to rest, digest, and relax.

The sheer demand for coffee is marked by the “queueing for coffee” in this haiku, which means there’s a long line of people waiting. Ironically, depending on the size of the business and the number of workers, people may have to wait for quite some time to buy their coffee. The fast-paced lifestyle is starkly contrasted with the elderly man, who is slowly counting his change and has to move at a much slower pace due to his age. This elderly man could be addicted to coffee, but he is not moving as fast as he used to. Alternatively, he could not be addicted to coffee at all. He may also be living in poverty due to counting his change. It seems people are waiting in line longer, partly because he is counting his change. Unfortunately, he may not have enough money to buy the coffee he ordered. I feel compassion for this elderly man and appreciate that he’s showing a slower pace of life. Also, the word “change” can refer to how the elderly man has transformed over his lifetime. The double entendre in haiku is a common device that is used to great effect.

According to Coffee Industry: Size, Growth, and Economic Impact Analysis, “The coffee industry is one of the largest and most influential sectors in the world, with an economic impact that extends far beyond just a daily beverage. As of 2025, the global coffee market accounted for $256.29 billion, and will register a CAGR of 4.52% from 2025 to 2034. This consistent growth reflects coffee’s enduring popularity, driven by changing consumer preferences, increasing disposable incomes, and the expanding coffee culture in emerging markets. According to a recent study, U.S. coffee consumption has grown by 5% since 2015, illustrating the increasing demand for this beloved beverage. This includes the shift toward premium and specialty coffee, which is boosting the value of global coffee beans, expected to reach $174.25 billion by 2030. Despite these hurdles, the coffee industry remains a crucial economic force, providing over 2.2 million jobs and generating more than $100 billion annually in wages across the U.S.”

According to Coffee’s Economic Impact:

“Two-thirds of American adults drink coffee each day and more than 70% of American adults drink coffee each week.”

Highlights of coffee’s economic impact in the United States include:

- The total economic impact of the coffee industry in the United States in 2022 was $343.2 billion, up 52.4% since 2015.

- The coffee industry is responsible for more than 2.2 million U.S. jobs and generates more than $100 billion in wages per year.

- Coffee can only be grown in tropical climates. It cannot be grown in most of the United States and is sourced from countries with tropical climates. Every $1 in coffee imported to the United States ends up creating an estimated $43 in value here at home. Learn more about coffee and trade.

- Consumers spend more than $300 million on coffee products every day—nearly $110 billion per year.

For more information on coffee, including the roots of coffee in Ethiopia, fair-trade, global coffee markets, and the consequences of colonization and enslavement associated with growing coffee in certain countries, I recommend this interview with Phyllis Johnson, published in The Sun Magazine: https://www.thesunmagazine.org/articles/601-crop-to-cup

In short, this is an important haiku that sheds light on coffee, the consequences of a fast-paced lifestyle, and also inspires compassion as we age.

a story

cut short

earthworm

— Bonnie J Scherer (USA)

Modern Haiku 56.3

Commentary from Nicholas Klacsanzky:

I believe this poem hovers between being a haiku or senryu—not that it matters too much. Ultimately, what is important is that it expresses violence and empathy via brevity, with its emotionality implied rather than stated.

Opening with “a story” is unique. As an editor, I don’t think I’ve ever seen that as a first line in a haiku/senryu. The phrase invites expectation and makes the reader curious about what is going to happen next in the poem.

“cut short” functions as both a poetic turn and a literal act. It interrupts the promise of “story” and physically refers to severing something. So, you got a balance between abstraction and the mundane.

With the mention of “earthworm,” we get the conclusion and also the opening up of the story. It grounds the poem in reality. This toriawase—story versus earthworm—creates resonance between human meaning-making and a small, often-overlooked being. The poet doesn’t dive into sentimentality; the earthworm is not anthropomorphized, yet the simplicity of the verse allows us to recognize that even the humblest organism contains a “story.” The violence is understated, yet it is heavy through sparseness.

I think the poem plays with the idea of impermanence and permanence. It is commonly known that if you cut off the body of an earthworm and the head remains, many times earthworms can grow their tails back and be whole once again. In this sense, the poet may be saying that even if a story is cut short, there is a strong chance that the narrative will continue with time.

Even though the poem is very short (five words in all), the sense of sound is strong. The elongated “o” sounds make the reading slower and more meditative. The “r” sounds perhaps bring extra weight.

I am a sucker for haiku and senryu that deal with the small things and beings around us, and this poem called out to me for that reason. The hidden meanings in the poem also made me more invested in it and allowed my mind to wander in introspection. A fine, sparse ku that does a lot with only five words.

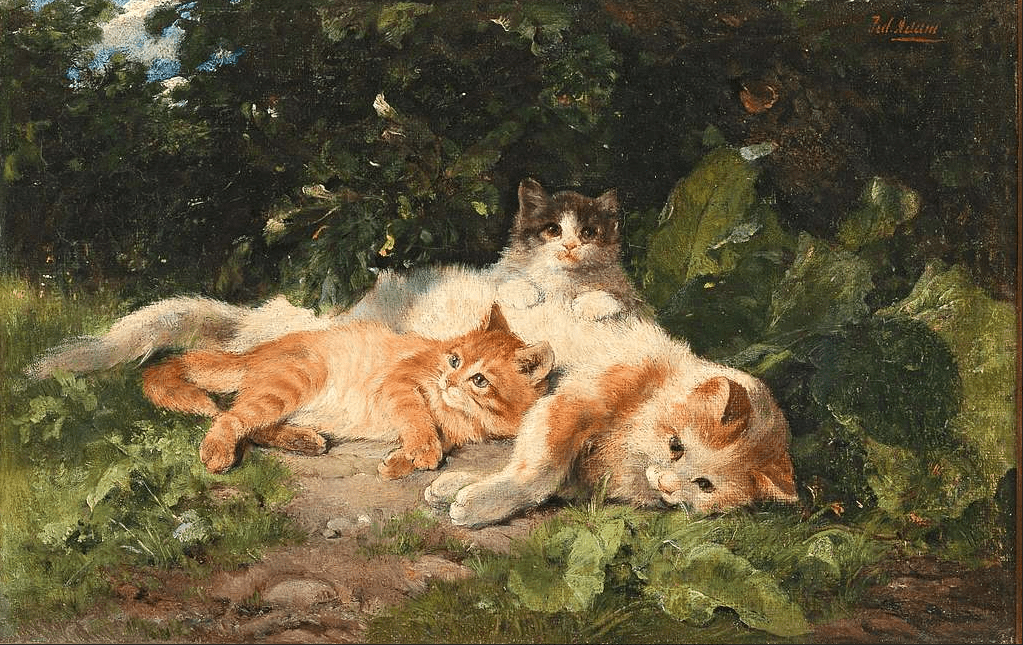

Painting by Julius Adam (1852 – 1913), “Cat with her Kittens”