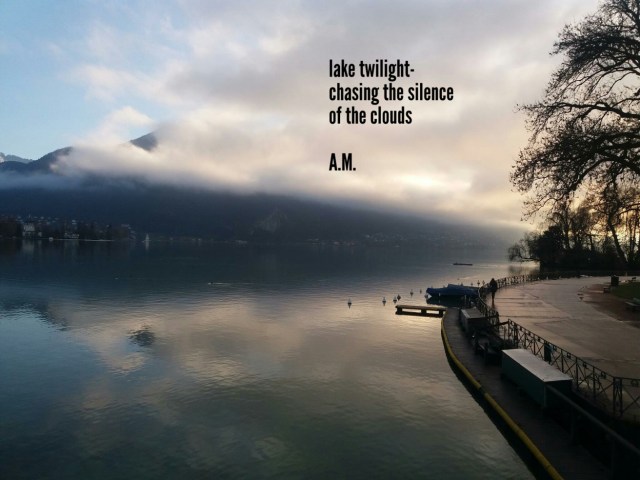

Photograph by Lorena Campiotti, haiku by Anna Maria Domburg-Sancristoforo

Photograph by Lorena Campiotti, haiku by Anna Maria Domburg-Sancristoforo

Published in Failed Haiku, issue 28, 2018

I enjoy the mystical sense this haiku brings. With the comparison of twilight at a lake and the chasing of clouds’ silence, the reader looks through their mind’s eye to imagine a meditative experience. The poet is perhaps wanting to leave her ego behind and become one with something more primal and foundational: the silence of nature.

Twilight is a time of being between daylight and darkness—something difficult to grasp or pin down. The “chasing” of the silence that clouds contain, either by the narrator or twilight itself, is another thing of abstractness and obscurity. This is akin to the Japanese aesthetic of yugen, which suggests subtle profundity and is associated with mystery.

The structure of the poem fits the rhythm of traditional haiku well and has a clear cut marker (kireji) in the first line to bring about more complexity and a juxtaposition. The strongest sounds in the haiku are the “l”s and “i”s. Both supply us with a lilting feeling, which in an abstract sense is like the movement of clouds.

The photograph conjures an epic scene to take in and sets the environment well. It compliments the haiku, as it does not go directly into the “chasing” part. It delivers the scene to us so we can dive more into the mind of the poet.

– Nicholas Klacsanzky (USA)

The opening line of this haiku takes us to the colourful sky that can be observed at twilight. Mostly, twilight has fading colours i.e. red, purple, yellow, and blue. These fading colours reflect the colours of an aura that we have in the evening, especially at twilight. So, the lake’s twilight complements or blends with the colours of our aura. I can feel the deep silence of the lake at twilight that is due to either the migration of birds or other lake creatures, or due to abandonment. In both cases, the lake reflects the colours of twilight, as well as the mood of the person who was observing it.

Chasing silence may indicate the meditative thoughts that are closely embedded in the silence of the lake and intertwined with the colours of the sky. The narrator may have had profound experiences of seeing clouds, which may also be her ongoing thoughts (maybe chaotic), and she wants to move beyond those thoughts to finally get a peaceful mind.

This haiku beautifully presents the whole image in a subtle way, where we can observe a deep relationship among twilight colours, clouds, silence, and mood. It reveals the mystery of human curiosity to go deeper into one’s thoughts and feel the depth of subtle experiences. Overall, I enjoyed the imagery of this haiku which moved me to vividly experience a lake twilight.

– Hifsa Ashraf (Pakistan)

If you enjoyed this haiku and commentary, please leave us a comment.