rush hour

the paper bag

crossing the street

— Ingrid Jendrzejewski (UK)

April 2024 at Cafe Haiku (Cityscape series)

Commentary from Hifsa Ashraf:

The opening line makes this haiku quite interesting. ‘Rush hour’ is now a new normal, where everyone is trying to meet the requirements of a fast-paced life. No ellipses after it may mean it’s open to interpretation. Everyone can fit in the scene according to their daily routine. It can be jobs, errands, studies, meet-ups, business, events, etc. In any case, the time is crucial and significant. The ‘sh’ sound in ‘rush’ highlights the urgency of work, while the silent ‘h’ in ‘hour’ shows how quickly it passes without letting us be aware of it.

The second line shows us those priorities that are usually not significant enough but keep poking us throughout the day. These priorities or tasks may distract us or deviate us from our main focus. ‘The’ before ‘paper bag’ refers to a specific bag or an analogy to our materialistic life that may be hollow and empty yet chaotic as well. This also indicates the mess around us that makes our life more complicated as mentioned in the third line of this haiku.

Crossing the street, or crossing our path, prompts us stop or slow down the ‘rush hour’. This could also relate to ceasing our thoughts or feelings. It also means that sometimes certain irrelevant things become relevant even if we are not paying much attention. This is how delicate our lives are. This is how emptiness or loneliness behind a fast-paced life keeps following us or crosses our paths. We realize that our relevance is defined by our attitude towards life.

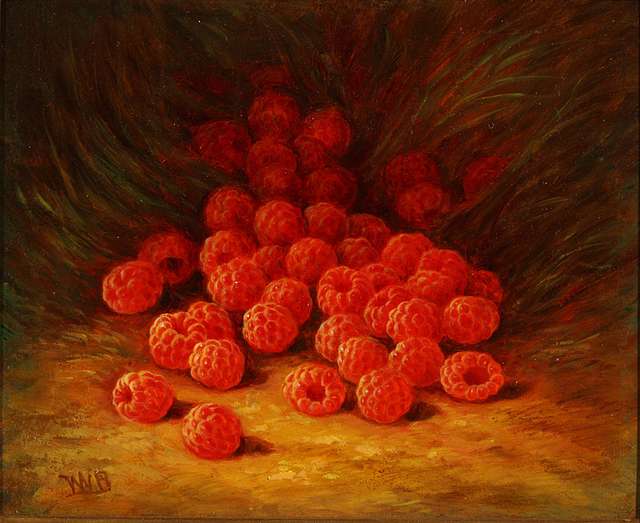

raspberry fenceline

a neighbour asks

how many kids in the plan

— Joseph Howse (Canada)

Kokako 42, April 2025

Commentary from Jacob D. Salzer:

An effective haiku that speaks of boundaries, social dynamics, and responsibilities. The first line is unique in that the fence itself could be the raspberry vines. Alternatively, the raspberry vines could be growing against an actual fence, and perhaps over the fence. The imagery and scent in the first line include both the sweetness of raspberries and the thorns of their vines that are likely entangled. This creates a powerful juxtaposition because we can imagine the tangled raspberry vines as being a metaphor for the complexity of relationships. In addition, there is a correlation between the plants growing (and the raspberries ripening) and the children growing and maturing over time. Will the children eventually climb over the neighbor’s fence? There is some potential humor in this haiku as well. Indeed, the neighbor’s question in the third line seems to signify a mental preparation for more babies and children in the neighborhood. I imagine a young couple buying their first house and talking about having children, which is a deep conversation that requires a lot of careful thought and planning. The last two lines could also imply that the neighbor may offer to help raise their children and support the family over the years. In summary, this is an interesting and effective haiku that speaks of boundaries, planning, responsibility, and the complex dynamics of social life in neighborhoods. A well-written haiku.

a sentence without punctuation desert silence

— Srini (India)

Kingfisher Journal, issue 10, 2025

Commentary from Nicholas Klacsanzky:

The concept of this haiku is clever. It discusses a sentence without punctuation and also presents itself as such. The word “sentence” can have dual meanings: a syntactical construction and what a criminal receives (or an innocent person sent to trial) as a punishment. Having “a sentence without punctuation” could refer to a person sentenced to life in prison.

Being a one-line haiku, it can be read in multiple ways: “a sentence without punctuation/desert silence”; “a sentence/without punctuation desert silence”; “a sentence without punctuation desert/silence”; and read as one flowing thought. The most natural, in my view, would be to read it as “a sentence without punctuation/desert silence.” However, each reader may approach it intuitively in different ways. Either way, this haiku shows a strong bond between human linguistics and nature. Another perspective is that this haiku is a contrast between something fabricated (language) and something standing alone in itself (the desert).

There is no kigo or seasonal reference per se, but “desert silence” does point to a certain time. It is most probably at twilight or early morning in the desert. This has an interesting potential for resonance with the idea of a sentence. A sentence is something formed and could relate to these times when life is waking up or is unclear.

Looking at the sound, I enjoy the letters “s” and “c” being reflections possibly of the hiss of sand. The letter “t” also has a finality to it that could connect to the context of a sentence or desert silence.

This haiku follows the principle of brevity with only six words present. Basho spoke of the necessity of haiku having no hindrance for the reader, yet there is deep meaning. I believe this haiku strikes this chord. It is one of the few haiku I have seen use the word “silence” successfully without me flinching, as often the word is employed in a cliche or lazy fashion. Srini has written a haiku that is at once natural and linguistic, which comes full circle in the context of the poem.

Red Raspberries on a Forest Floor by William Mason Brown, c. 1866, High Museum of Art