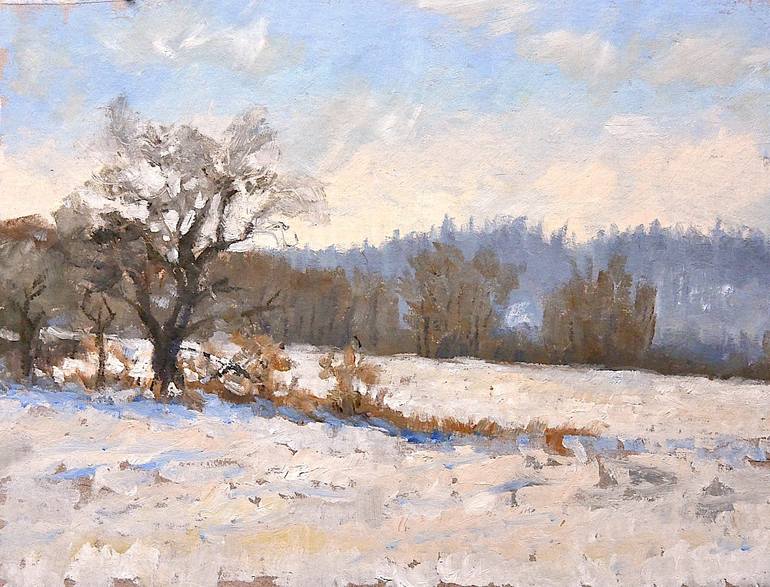

in the apple tree

a nest full of snow

the wind’s soft whistle

— John Hawkhead (UK)

(Presence magazine, issue 70)

I appreciate how this haiku depicts the cycles of life, and also hints at life after death. I feel the last line could be (or include) the spirits of the birds. The contrast of the warmth that was once present in the nest with the stark cold snow gives me a feeling of impermanence and letting go. I also interpreted this haiku as a metaphor for human families when children go off to college and the parents become “empty nesters.” The children’s bedrooms become empty and are sometimes remodeled for other purposes. It seems emptiness is what allows life to become full. Even if the glass is empty, I see this as a creative space, filled with possibilities vs. an absence devoid of life.

I miss the presence of birds in this haiku and their songs. They may have passed away long ago, or simply migrated to another tree that provides more protection. However, despite the winter season, the main feeling I get from this haiku is gratitude, acceptance, and beauty in the mystery of both life and death. I get a sense that when winter fades to spring, perhaps at least part of this nest will remain for future bird families.

All this being said, I feel a combination of melancholy and abundance in this haiku at the same time. I also appreciate how this haiku engages our senses. I can smell the snow in this haiku. I can even smell the apples from past seasons. I can hear the wind and the memories of birds singing that are also linked with other memories. I can feel the coldness in my bones, and the reassurance that even in death, life goes on. A beautiful haiku.

— Jacob D. Salzer (USA)

This haiku starts with a tinge of mystery where the poet takes us to the ambience that is only observed by those who focus on the intricacies of nature. ‘Apple tree’ is often symbolized as a sacred tree or a tree of love, which makes the opening line more significant by pausing our thoughts for a while.

Visualizing a nest full of snow on an apple tree gives an idea of ‘filling the void’ in life where snow as a temporary and the most delicate phase may either project abandonment, emptiness, melancholy, and loneliness or replacement, the yearning of dreams, and hope. In both cases, it shows how fragile and uncertain this life is when one does not remain productive. The wind’s soft whistle gives some hope and positivity besides the melancholic imagery of this haiku. It also indicates the continuity or flow of life even in the most unfavorable circumstances.

From apple tree to soft whistle, this haiku gives a holistic picture of different phases of life and nature that are interconnected and depend on each other for survival. I also see this haiku as an incubation period of creativity where the poet as an observant seeks solace in the delicacies of nature by synchronizing all thoughts and feelings.

— Hifsa Ashraf (Pakistan)

Jacob and Hifsa discussed the meaning behind this haiku well. I now want to delve into the more technical aspects of this poem.

The thing I noticed first was the lack of punctuation in the second line. The break between the two parts is defined by the line break, though. If it were me, I might have added an ellipsis. However, nothing is taken away from the haiku due to a lack of a dash or ellipsis to act as kireji.

The kigo is easy to identify with “snow.” The desolation of this season is expressed even more in the third line.

Though there are three articles in this haiku, each one is used appropriately and meaningfully. Concision and brevity play a large part in the success of this poem.

In terms of sound, a lot is going on that helps the haiku read well. The “l” and “o” sounds are the most beautiful, bringing a lilting feeling and a softness if read out loud. In contrast, the “i” sound displays starkness that coincides with the imagery.

The last line for me is the most significant. The whistle can be a chilling reminder of the fragility of life and its harshness. It can also be a tribute, a soothing song, or nature being playful despite the circumstances. The poet leaves the interpretation up to the reader.

— Nicholas Klacsanzky (USA)