luminescent sea

all the little things

we think we’ll remember

— Sam Renda (South Africa)

Published first in Autumn Moon Haiku Journal, Issue 5:2, Spring/Summer 2022

Commentary by Jacob D. Salzer:

This is a powerful haiku that allows readers to contemplate the mysterious phenomenon of individual and collective memory. In addition, this haiku sparks several meaningful conversations.

The first line of this haiku is a powerful image, and also sets the mood and tone of the poem. The sea is vast, while human memory is limited. To that end, this haiku could be foreshadowing different forms of memory loss, including Alzheimer’s disease and/or dementia. With this in mind, this haiku seems to be encouraging us to take preventative measures to reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s and dementia as we age. For more information on doing our best to prevent Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, I recommend reading Reducing Risk for Dementia, and also discovering the neurological and cognitive benefits of drinking green tea regularly at Brain-Protective Effects of Green Tea and Beneficial Effects of Green Tea Catechins on Neurodegenerative Diseases. In short, a healthy diet, physical exercise, meditation, and avoiding tobacco and alcohol can all help prevent memory loss down the road.

Interestingly, neuroscientists have discovered that what we call memories are inherently incomplete fragments that are filled in subconsciously by our imagination. For more information on this fascinating subject, I recommend these two articles: Memory and Imagination: Exploring the Interplay Between Past and Future and How Your Brain Makes Up Stories to Fill in the Blanks.

Simultaneously, it seems this haiku is asking readers to contemplate what parts of our lives we want to document for our family and future generations. To put it more simply: what do we want to leave behind? Interestingly, on that note, this haiku could speak directly to the art of reading and writing haiku. In other words, as haiku poets, when we write haiku, we are leaving behind moments, traces of an experience, and documenting our lives in the ever-flowing “now” that seems to contain the entire past and the future within it. This leads to an interesting conversation on how personal haiku can be, and yet, how universal they can be as well. Do we want our haiku to allude to us as silent observers of life? Or, do we want to share parts of our seemingly private lives with others, including strangers? There seems to be a spectrum, and in our human lives, there seems to be room for personal as well as universal moments. In short, there appears to be room for our personal imagination, memories, and direct observations in our haiku writing that reflects the psycho-spiritual complexity of being human.

The notion of collective memory has been explored, perhaps most famously, by Carl Jung: “[The] collective unconscious: [a] term introduced by psychiatrist Carl Jung to represent a form of the unconscious (that part of the mind containing memories and impulses of which the individual is not aware) common to mankind as a whole and originating in the inherited structure of the brain. It is distinct from the personal unconscious, which arises from the experience of the individual. According to Jung, the collective unconscious contains archetypes, or universal primordial images and ideas” (collective unconscious).

This haiku also sparks a conversation about the history of this Earth and lost civilizations. For a fascinating dive into lost civilizations, I recommend these two articles: 11 Civilizations That Disappeared Under Mysterious Circumstances and 20 Lost Civilizations That Might Still Be Hidden Today.

Other spiritual teachers have sometimes used the term “Universal Mind” to describe Divinity. Interestingly, in terms of consciousness itself, it seems memory is infinite. With this in mind, returning to the haiku, poetically, the luminescent sea could relate to consciousness itself and the vast storage space that contains our memories. These memories could also include the memories of other species as well. This leads to an enriching conversation on the notion of past lives, reincarnation, and past lives that some children have remembered with evidence that strongly supports this, as they remember precise details. For more information on this subject, I recommend Children Who Report Memories of Past Lives.

Finally, with the invention of the internet and AI (artificial intelligence), I think we should be asking ourselves how we wish to be remembered in the digital world, think about how our memories are stored in digital ways, and find ways to protect and preserve what we choose to document and share. This can be a controversial and harmful terrain to enter, as there are many lawsuits involving artists and writers where AI companies have stolen or manipulated their original work and have violated copyright laws. For more information, here are two sources: Generative Artificial Intelligence and Copyright Law and AI giants are stealing our creative work. The limited memory space on a computer (and in the cloud) is also interesting when relating to the human brain’s capacity to store memories. Of course, with all this being said, The Matrix movie also comes to mind.

In summary, this is a highly contemplative haiku that encourages us to think deeply about memory, collective memory, our imagination, our identity, and what we each want to leave behind (and what we are collectively leaving behind).

autumn dusk —

the empty swing

still warm

— Vaishnavi Pusapati (India)

Published first in Autumn Moon Haiku Journal, 2025

Commentary by Hifsa Ashraf:

The opening line, “autumn dusk,” pauses me for a moment, allowing the scene to settle. Autumn dusk is often associated with sadness, dullness, and gloom; yet, this perception depends on the setting: a park, a school ground, a family courtyard, a garden, or a village home. Dusk is a threshold, a fragile pause where traces of the day still linger before transforming into night. In autumn, it reveals its truest colours, evoking nostalgia, melancholy, solitude, and quiet reflection. The em dash deepens this pause, suggesting the person is drawn into this moment by vivid memories or sudden flashbacks.

The second line introduces a sense of loneliness through the image of the empty swing. It becomes an object of remembered joy, perhaps of childhood, perhaps of a cherished phase of life that comes back time and again. The swing once held laughter, motion, oscillation, and presence; now its emptiness mirrors the inward sense of loss and longing. The space before the second line depicts the depth of emptiness and loneliness one is feeling at the moment.

The concluding line, “still warm,” gently shifts the emotional temperature of the haiku. Against the cold, muted tones of autumn dusk, warmth suggests recent human presence, someone who has just departed but has left behind fresh, tender memories. The word “still” implies continuity: memory has not faded with time. Warmth here becomes emotional rather than physical, affirming that no matter how distant the past, deeply held memories remain vivid and alive.

I especially admire the interweaving of cold and warmth, absence and presence, without making the poem explicit. Even the recurring m sounds subtly contribute to a sense of mystery, intimacy, and inward reflection—echoing the quiet depth of lived experience.

feather dance

in the twilight

childhood wonder

— John Tang (China)

Commentary by Nicholas Klacsanzky:

The first line, “feather dance,” caught my attention right away. It made me think of Native American and Oaxacan dances to honor gods and ancestors. Since the poet is from China, I conducted a little research on the Chinese Feather Dance, which is a tribute to ancestral temples or the Gods of the Four Directions. The dance was used in imperial or official sacrificial ceremonies, particularly during the Zhou dynasty’s court music and dances, known as Yayue. In China, feathers in ritual dances often represent the ability to soar, connecting the Earth with the divine or sky gods.

However, I think many readers will read “feather dance” as a single feather falling and twirling down to the ground. Given that we mostly see feathers as already fallen, witnessing one drift down from the sky is an awe-inspiring moment.

With the introduction of “in the twilight,” the haiku becomes more mysterious and mystical. Twilight is often when clarity softens, and imagination can breathe. It’s a fine setting for a feather to feel more enchanted rather than incidental.

The final line, “childhood wonder,” names the emotional resonance, but it doesn’t feel heavy-handed because it arrives after the image has already done its work. I also take it as a comparison between the feather’s dance in twilight with childhood wonder as a concept. The awe we feel in our childhood dies down when we become adults, but we can try to revive it. This could be seen as a dance or a beautiful oscillation.

With no punctuation in the haiku, the second line could be seen as a pivot. The poem can be read in two ways: feather dance/in the twilight, childhood wonder, or feather dance in the twilight/childhood wonder. So, twilight can relate either to the feather dance or childhood wonder, or both.

Within the fitting brevity of the haiku, there is also a strong sense of sound, with lilting l and i, as well as pounding d, which creates a juxtaposition between beauty and stark awe.

A lovely cultural haiku that resonates far beyond borders.

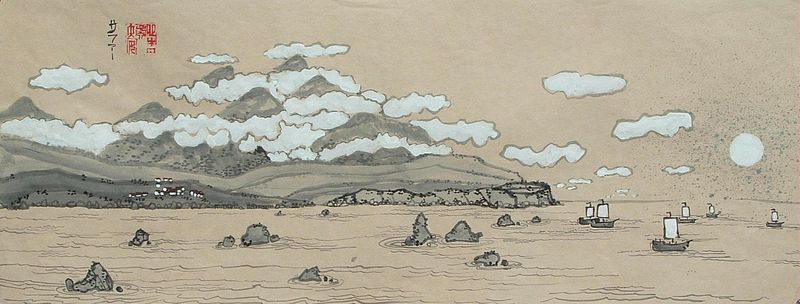

Painting by Dawn Hudson