starlit pond…

a paper boat floats

for light years

— Srini (India)

Tinywords, 25:2, October 3, 2025

Commentary from Hifsa Ashraf:

This haiku transports us into a quiet, enclosed space—perhaps a park, a backyard, or a secluded garden. The opening image is enchanting and dreamy: a starlit pond blurs the line between sky and earth, mirroring the cosmos in its still waters. The ellipsis at the end of the first line invites a pause, allowing the reader to absorb the magic of the moment. I can almost see a tapestry of stars delicately reflected on the pond’s surface.

The second line introduces a subtle shift: a paper boat floats on the water. It acts as both an interruption and an anchor—drawing us back from reverie into something tangible and innocent. The boat may symbolize a small dream, a fleeting hope, or a playful childhood memory. Its fragility contrasts with the vastness of the sky, evoking a sense of childlike wonder and gentle yearning.

The closing line, “for light years,” broadens the scale dramatically, allowing us to feel the vastness of our universe. This simple phrase goes beyond time and space, suggesting a desire for an unending journey or an unreachable dream, sort of imaginative, but still holds some meaning. It transforms the scene into something meditative—where a single paper boat becomes a bridge between the earth and the cosmos, a bridge that also connects a dream with reality. It seems one is thoroughly enjoying the surreal environment that inspires them to see beyond limited vision and express one’s longing in the most beautiful and innocent way.

the mosquito mesh

pixelating

the night

— Danny Blackwell (Spain)

NHK TV program Haiku Masters, July 31, 2017. Reprinted in tiny words 17:2

Commentary from Nicholas Klacsanzky:

With the mention of “mosquito,” we could be receiving a kigo (seasonal reference), as they are most active during the warmer months—especially in June and July. Summer, as it relates to pixelation, can be likened to something overwhelming.

There is no explicit kireji (marker for the cut between parts in a haiku), but the line breaks act as a quasi one. The flow of the haiku can be read as one part, yet it is broken down as a pixelated mesh would be. This brings the reader more into the “space” of the poem.

The mosquito mesh is dual-acting: keeping out mosquitoes but also a catalyst for altered perception. As a person who used to work in information technology, I have often thought about the poetic implications of mesh and it being like pixelation. It is a visual metaphor drawn from the digital realm that plays with mundane texture. The mesh breaks the darkness of night into fragments, perhaps making it more manageable and less oppressive. This toriawase (combination of elements to create harmony) of the analog and digital invites multiple readings, with the word “night” having physical and metaphysical implications. “Night” could be indicative of a sadness, a horror, or a malaise.

The mesh could also be illustrative of the distance between intimacy and separation. The poet is close enough to notice the effect of the mesh, yet the mesh itself signifies a boundary between inside and outside, human and nature, the safe and the wild. It is a contemplative image that captures the modern condition: the world increasingly filtered, fragmented, and mediated through invisible grids.

With the repetition of t and i sounds, I can almost hear the tick of mosquitoes against the net and their whining. Overall, it is a haiku that expresses succinctly and poignantly a bridge between technology and the natural world, and the false divide we put up between nature and humanity.

emergency room

an elderly patient

rocking back and forth

— Tuyet Van Do (Australia)

Pulse, 19th September 2025

Commentary from Jacob D. Salzer:

The emergency room (ER) is a tough place to be, for a variety of reasons. While there is a triage process that’s designed for providers to first see patients with the most severe injuries and diseases, a lot of people end up in the waiting room for anywhere between 2 to 3 hours (or sometimes more) before being seen by a provider. The ER can be a crowded place. I’m personally a strong advocate for preventing diseases and injuries, though some things are hard or impossible to avoid. In this senryu, I first saw the ER waiting room full of people, and then noticed the elderly patient rocking back and forth. This movement could help create a soothing rhythm in the midst of what is often chaos and uncertainty. The elderly person could be rocking back and forth as they wait for the doctor or test results. While the ER can be a very difficult place to be, it’s also often a place of healing, recovery, and discovering what’s gone wrong.

We don’t know what the patient is going through in this senryu, but when I read this poem, I immediately feel compassion and empathy for the elderly person and for the human condition. It’s never easy being human, and it gets increasingly more common for things to go wrong in the body and mind as we age.

While this poem may seem simple on the surface, there are layers of psychological and medical complexity that I appreciate. A well-written senryu that offers a portal into another world.

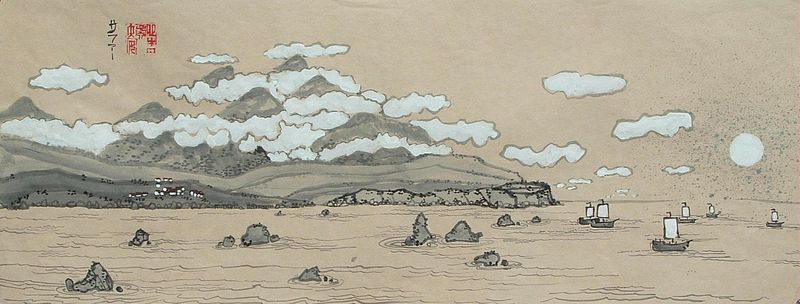

Painting by Hisae Shouse