lockdown

in the flight of a seagull

a little sea

— Francesco Palladino (Italy)

The current lockdown has changed our lives so much. We see new dimensions or unique perspectives often. This may be due to shifting from one normal to another which is original and profound in many ways.

In this haiku, the writer finds a subtle yet vivid moment where he feels the delicacy of existence in a beautiful way. The flight of a seagull seems to indicate a set direction in life or set objectives that one has planned before or during the current pandemic. It can also mean that the person has gained maximum mindfulness, where he accomplished his objectives or has had profound learning experiences. The ‘little sea’ to me shows a level of knowledge that is vast and/or an abundance of knowledge due to clear thoughts.

The other aspect of this haiku may be contrary to the above. Maybe, the lockdown and the self-isolation has disturbed the thought process of the narrator, where he lives in an imaginary world and finds his objectives merely an illusion or daydream about them instead of fulfilling them. The ‘little sea’ may be a mirage that comes our way during our daily routine and we seek solace in it until the lockdown is over.

Looking at the sound, the letter ‘l’ shows the stiffness or persistence of a thought process occurring during a lockdown.

— Hifsa Ashraf (Pakistan)

What I enjoyed immediately about this haiku is the pivot in the second line. It can refer to both the first and last lines. In a poem as small as a haiku, this is a powerful technique that creates more layers.

Thus, you can read it as:

1) lockdown in the flight of a seagull/a little sea

or:

2) lockdown/in the flight of a seagull a little sea

The first version is saying that the poet sees the lockdown in the flight of a seagull and he is comparing it to a little sea. The second version is giving the idea that a lockdown is like a little sea, which the flight of a seagull can show.

Both point to a similar theme, in my opinion: within the seagull, and perhaps within all of us, is a sense of isolation but also a grandness. This mix of feelings reflects in the autumn kigo of a seagull (though seagulls can ultimately refer to almost all seasons).

It is interesting to note the use of articles. Employing “the” with “flight” puts a focus on the act of the bird rather than the creature itself. It gives readers something to nibble on in terms of freedom/containment. In this time of quarantine, we struggle to have even basic freedoms.

“a little sea” could be metaphorical but also physical. The seagull could still be wet from a dive or some seaweed could be clinging to its wings while in flight.

As Hifsa noted, the “l” sounds in this haiku work well. I have a bit of a different take, though. I feel this letter in the poem provides a sense of the seagull lilting on the wind, free and at ease.

It seems Palladino is espousing the concept that freedom is present even when we are in a lockdown or have our movement restricted. That we should find inner joy even when our environment becomes demarcated.

— Nicholas Klacsanzky (USA)

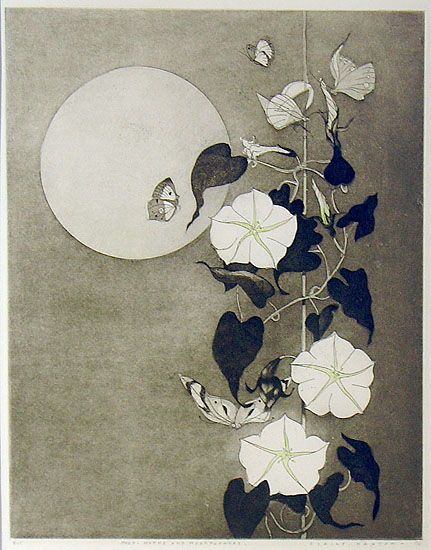

— “Three Seagulls” by Ohara Koson 1900–1936